Reports

Technology, media, and telecommunications predictions 2020

A parallel phenomenon is underway in the technology, media, and telecommunications (TMT) industry. Only 10 years ago, for instance, each kind of artificial intelligence (AI) technology was its own sapling – innovations in natural language processing did not lead to better visual recognition. Then, new deep machine-learning hardware began to accelerate all AI innovations at the same time, creating a canopy in which advances in one area were almost always matched by advances in the other (former) AI silos. Nor does the phenomenon stop there. Until recently, deep learning has been performed using chips that cost thousands of dollars and use thousands of watts, and that was hence largely restricted to data centers.

Just five ecosystems are responsible for the bulk of the TMT industry’s revenue. The smartphone ecosystem alone is worth well over a trillion dollars per year. The TV ecosystem is worth more than USD 600 billion; PC sales and ancillaries (consumer and enterprise) generate yearly revenues of about USD 400 billion; enterprise data centers and software (combined) will make about USD 660 billion in 2020; and IoT (accelerated by the rollout of 5G) will be worth half a trillion dollars by 2021. If other newer devices – smart watches, consumer drones, e-readers, home 3D printers, AR glasses, VR glasses, and smart speakers – are added up, their combined ecosystems generate only a small fraction of the smallest of these big five.

My antennae are tingling

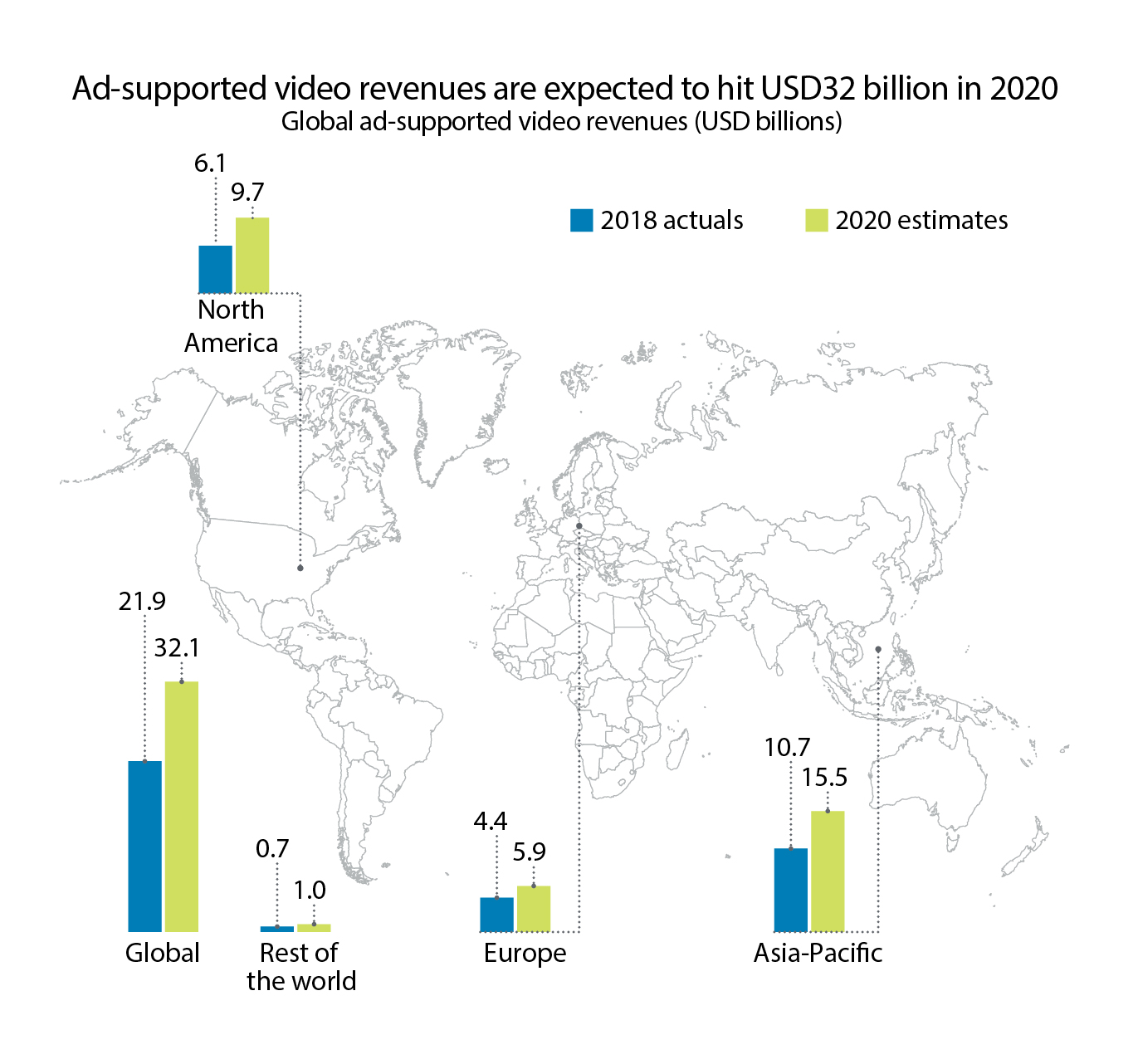

Along with a predicted USD 32 billion in 2020 revenue from ad-supported video-on-demand (AVoD), antenna TV is helping the global TV industry keep on growing even in the face of falling TV-viewing minutes and, in some markets, increasing numbers of consumers cutting the pay-TV cord.

Who is paying for all that free TV? Advertisers. The global TV ad revenues will grow by more than USD 4 billion in 2020, reaching USD 185 billion in 2021, compared to USD 181 billion in 2019. In terms of magnitude, this market size change is not wildly out of line with general consensus, but the direction we expect it to take is different. While some are anticipating TV ad revenue to fall by USD 4 billion between 2018 and 2021, it will grow by about the same amount.

Why do TV antennas matter? A Mexican broadcaster in 2019 may have put it best: Broadcast on-the-air television is the most efficient media to tap the mass market. The sheer number of antenna TV viewers in an age of proliferating entertainment alternatives raises some interesting questions. First, just how big is the antenna TV market? Second, what headwinds does the overall TV industry face? And third, how and why is the TV ad market not only so resilient, but growing?

Deconstructing the TV industry

The TV industry consists of two basic types of companies – broadcasters and distributors. Distributors, whether pure-play or not, are the companies that today transmit all of the world’s TV content to viewers – except for the on-air programming broadcasters still make available through antenna TV. Broadcasters make most of their money from advertisers, who pay to place commercials on the broadcaster’s shows. Broadcasters also make some money from distributors, who pay broadcasters retransmission consent fees for including their channel(s) in the bundle. However, most broadcasters do not receive any money directly from viewers. Distributors, on the other hand, make almost all of their money from subscribers, selling bundles of channels to viewers. The distinction between broadcaster and distributor has been steadily eroding at the corporate level, as companies that started out as distributors bought up broadcasters and vice versa. In fact, the majority of the TV industry players in the world today are not pure plays – they are both broadcasters and distributors.

Sizing the antenna TV market

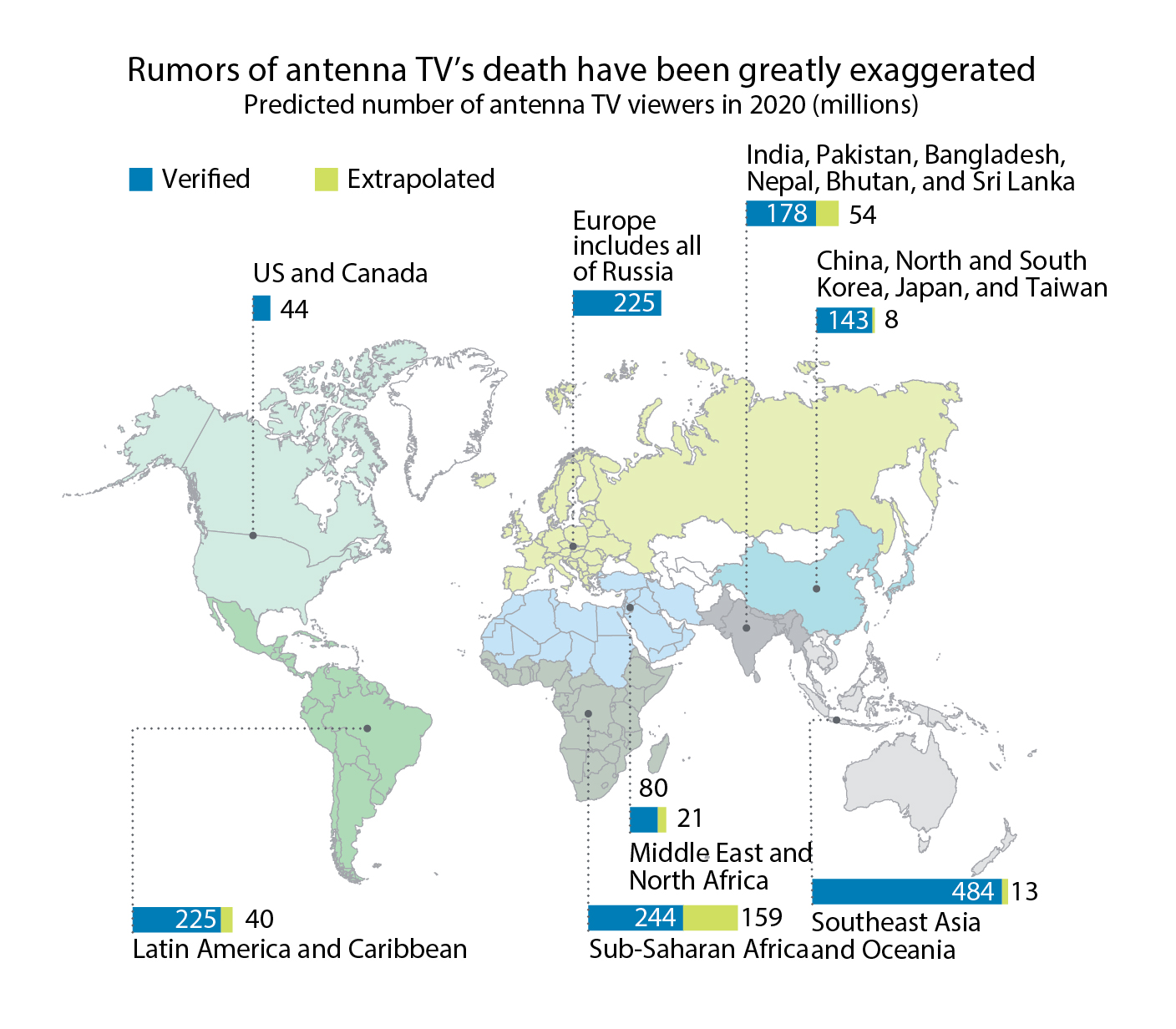

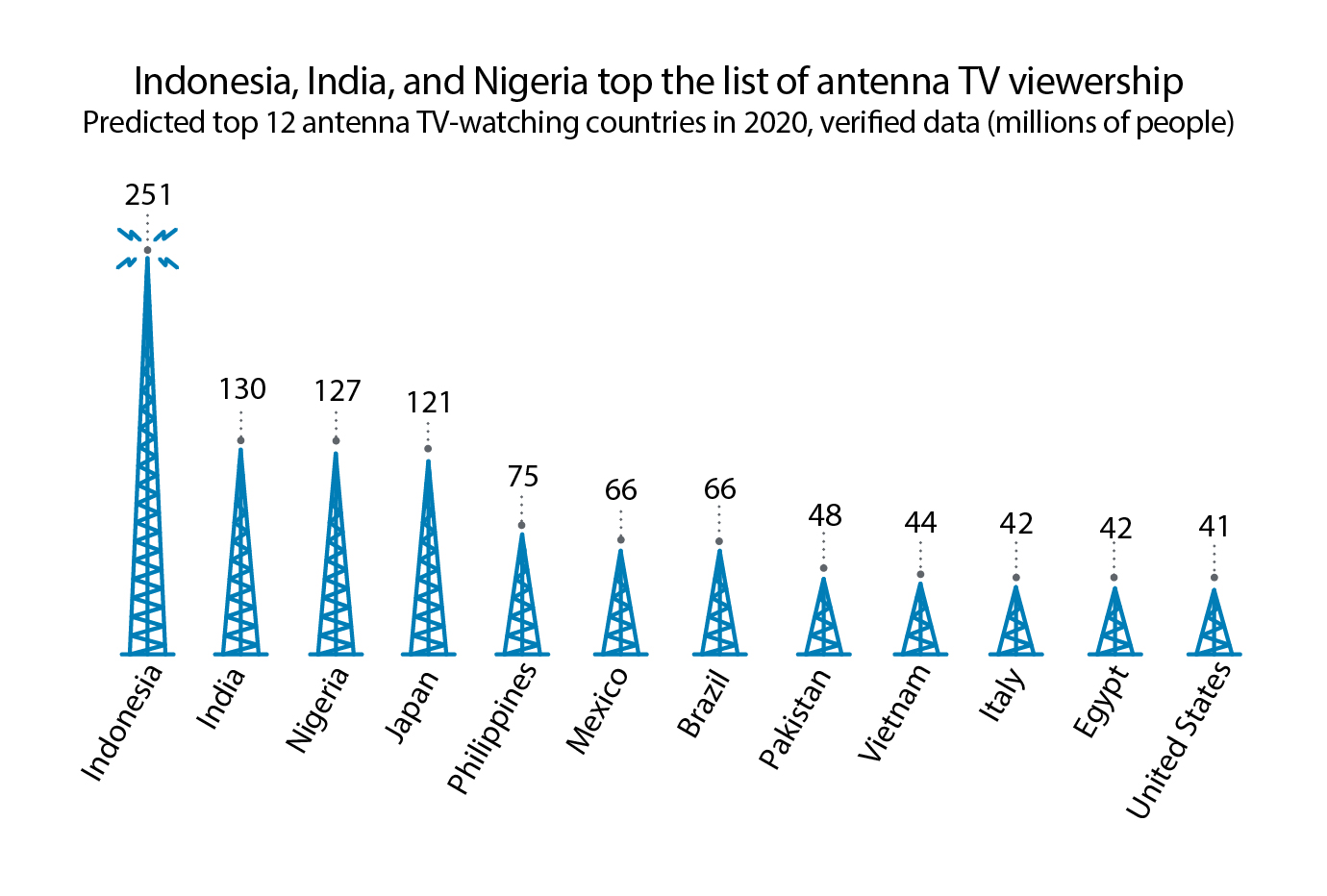

Deloitte’s estimate of 1.6 billion antenna TV viewers in 2020 is based on verified data from 83 countries with a combined population of 6.6 billion people. Of these, Indonesia, India, and Nigeria are expected to have the most antenna TV viewers. If it is assumed that countries that lacked verified data resemble their neighbors in terms of antenna TV penetration, the estimate of global antenna TV viewership in 2020 rises to a whopping 2 billion.

Not grandfather’s rabbit ears. But sometimes they are

Fifty years ago, TV antennas came in two kinds – the classic pair of rabbit ears that sat on top of the TV or roof-mounted UHF/VHF aerials. Depending on the market, both kinds of analog antenna are sometimes still seen today. Digital antennas have now also joined the mix. In markets with advertising, FTA broadcasts carry the full load of TV commercial advertising. Digital video recorder/personal video recorder (DVR/PVR) solutions exist. However, it is unclear how many antenna users worldwide also have a DVR/PVR box. This suggests that either very few antenna TV viewers own a recording device, or they do not use them very much. Assuming this trend applies to other countries, the implication is that time-shifted TV viewing – and, therefore, the ability to skip ads – among antenna viewers is dramatically lower than among pay-TV viewers.

The traditional TV industry can use antenna TV’s help

Antenna TV’s resilience is a bright spot in the overall TV landscape, as the traditional TV industry as a whole (pay-TV and antenna TV combined) is facing headwinds. Several signs in the US market point to challenging times ahead. Similar trends are afoot in other countries as well. Brazil, Mexico, Hong Kong, Canada, Sweden, Denmark, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, Israel, Venezuela, and Ireland all are seeing ongoing declines in pay-TV subscribers. TV viewership growth in the rest of the world more than offsets these declines, for now. The number of pay-TV subscriptions worldwide is expected to rise by 8 percent between 2018 and 2024, reaching 1.1 billion in 2024. But even though more people are subscribing to pay-TV, the industry as a whole still is not making as much money as it used to – global TV industry revenues are forecast to decline by 11 percent in 2023 compared to 2019.

Why are TV ad revenues still growing?

Advertisers are still showing faith in traditional TV. Some networks reported double-digit growth. Why are not things worse for broadcasters’ TV ad revenues, at least in markets where viewership is falling? Here, antenna TV may well be one of the factors making the difference. Antenna TV viewership is growing, or is at least stable in several large ad markets, representing tens of millions of antenna TV watchers who are not skipping ads while watching traditional TV. Besides antenna TV’s growth, another reason for TV advertising’s resilience is the development of targeted or addressable ads. If a home has the right kind of box or TV advertisers can deliver specific ads to specific households at premium rates. These ads are helping the TV industry to offer advertisers features, such as personalization and viewership measurement that previously were possible only with digital ads, as well as drive much higher prices per thousand views. The final factor contributing to TV ad spending is that the ongoing shift to digital ads of all types is not a one-way street. Although digital has been growing, and is expected to continue growing, individual ad buyers are constantly reallocating their spending between digital and TV; but TV and digital combined are expected to represent just under 80 percent of global ad spending by 2021. Several studies suggest that the choice is not binary between TV and digital; rather, advertisers should find a mix of the two that work together. Given that some companies in recent years have gone all in on digital, it is not surprising that some dollars – billions of them – may be coming back to TV worldwide.

Coming to a CDN near you

The global content delivery networks (CDNs) market will reach USD 14 billion in 2020, up more than 25 percent from 2019’s estimated USD 11 billion. Further, the market will double to USD 30 billion by 2025, a CAGR of more than 16 percent. This growth is being driven primarily by consumers’ ever-increasing hunger for streaming video over the internet, now amplified by the migration of more broadcast and cable TV onto D2C OTT internet delivery networks. However, it is not certain exactly who will cash in on all this growth, as bigger media, cloud, and telecom players develop or expand their own CDNs. Their success may threaten profits for existing CDN providers even while increasing demand for the hardware and software capabilities necessary to deliver so much media.

Video goes over the top

The largest driver of growth for the CDN market has been, and will likely continue to be, the rising demand for video over the internet. The internet, of course, is not the only way to watch videos; many other video-delivery technologies, ranging from old school on-air broadcasting to cable, DSL (copper phone lines), and private IPTV networks, are still in use today. However, to keep up with evolving consumer behavior amid an explosion of mobile devices, as well as the advertising dollars that follow large numbers of eyeballs, digital media delivery has been expanding from private IPTV networks into OTT networks that run over the internet. This expansion into OTT has at once enabled and been a response to much higher internet usage and greater broadband penetration.

OTT streaming video uses over 60 percent of global internet bandwidth, according to Sandvine. Netflix already uses an estimated 15 percent of global downstream internet traffic, and a single top streaming video service can consume up to 40 percent of downstream traffic on some regional operator networks. Fueling all that video traffic is continued growth in SVoD. With several major new SVoD services launching, global subscriptions to streaming services could grow significantly. The resulting increase in OTT video traffic, however, would not necessarily drive greater revenues for specific CDN providers. Much of the growth in video traffic comes from the largest SVoD services, social networks, and other hyperscale digital media companies that already operate their own CDNs. Furthermore, the largest media companies entering the SVoD space may eventually build their own networks or, in some cases, use the networks they already control.

Although the current SVoD expansion is being led primarily by US-based media, some see global networks as a path to unlock global markets. APAC is expected to account for 51 percent of all video streaming traffic by 2024, almost twice as much as in 2018. Some US CDN providers offer CDN services in Asian markets, and some leading Chinese CDNs now host over 1000 PoP nodes across the country, with additional networks in other Asian countries. However, content delivery in Asian markets can be challenging due to sparse coverage and limited mobile network.

It is hard work making it easy to watch a video

The growing quantity and sophistication of OTT video content means more traffic, more routing, and a greater need for management, optimization, and prediction across the CDNs responsible for delivering speedy and reliable content. From a technical standpoint, live and on-demand video streams move a lot of bits to render high-resolution images. Streams need buffering and caching to avoid lags and dropouts. Legacy protocols such as real-time messaging protocol (RTMP), developed over a decade ago to encode video and move it across networks to clients, will likely be displaced by newer solutions, such as secure reliable transport (SRT), designed to further decrease latency and meet the demands of live and on-demand streaming. Live video streaming, in particular, can pose significant challenges for CDNs. By some estimates, live video streams in 2018 accounted for 11 exabytes (EB) out of a total 58 EB of CDN video traffic; by 2024, live streaming is expected to account for as much as 238 EB out of a total of 453 EB – or half of all video streaming. As the audiences for live streaming services grow, so too should CDNs.

Ad-supported video

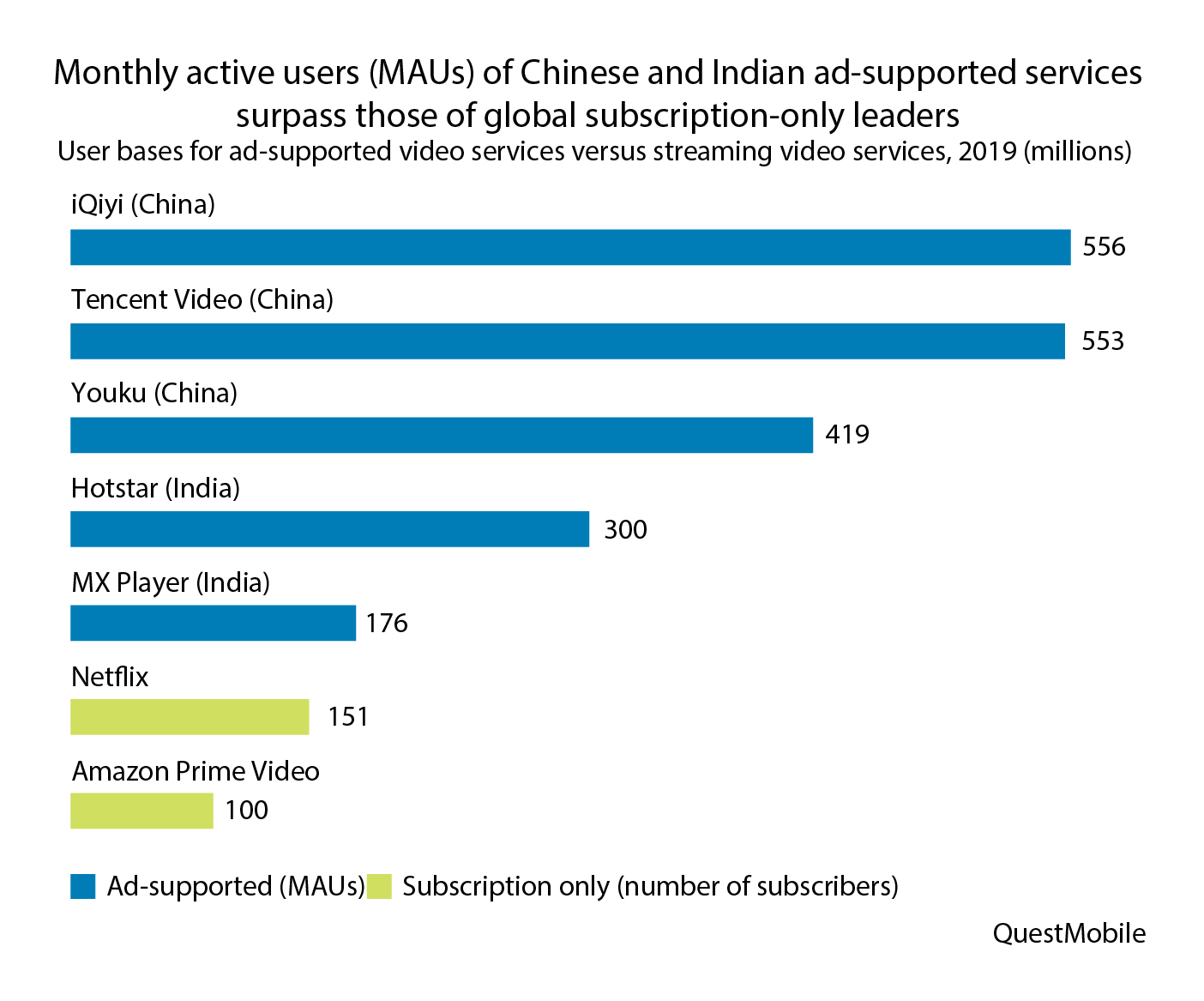

In China, India, and throughout the APAC region, ad-supported video is the dominant model of delivering streaming video to consumers. Sometimes, it is combined with subscription services; in other cases, revenue comes from ads alone. It is a big business that is poised for serious growth. Deloitte Global predicts that revenue from ad-supported video services will reach an estimated USD 32 billion in 2020. Asia will lead with USD 15.5 billion in revenue in 2020, nearly half of the global total. This prediction will document the rapid rise of ad-supported video services in Asia. Over a billion people in Asia watch ad-supported video services, thanks to the advent of affordable 4G connectivity, low-cost smartphones, and business models that allow consumers to exchange their attention for free (or low cost) TV shows, movies, and sports.

In the US, by contrast, most D2C video offerings are pursuing the ad-free subscription model that companies like Netflix have used to dominate the American market. As more TV networks, film studios, and tech companies launch their own subscription services, the fact that US consumers have an average of three such services – and are already frustrated – suggests that only a handful can thrive. Where does that leave the rest of the 300-plus subscription-based services competing for attention and wallet share? Could ad-supported video provide a model that brings consumers a greater variety of content in one place, at low (or no) cost? Could it offer a solution for advertisers looking for an alternative to the social networks and search engines that dominate the online ad market? Could it provide the basis for broad entertainment platforms that serve gamers, music buffs, sports fans, and everyone in between? If so, ad-supported video could be the latest successful Asian import to the US.

The Asian model

In Asia, the number of people who watch ad-supported video services is staggering: The user base of several leading services reaches nearly half a billion. Most of these services were launched after 2010. They have grown so big, so quickly, by making it easy for cost-conscious consumers to monetize their attention – essentially converting time spent watching ads into content they would otherwise have to pay for. Many of the biggest ad-supported services are pursuing similar strategies to scale quickly and expand their sources of revenue.

The elements of Asian model can be seen in action by taking a closer look at one of the world’s biggest ad-supported markets: India.

India: Ad-supported video puts TV into the hands of millions

Pay-TV in India is inexpensive, and in some states, nearly 90 percent of households have a TV. Hotstar is the leader in India, but competitors from TV networks, telcos, and foreign streaming services (including Netflix and Singapore-based HOOQ) are fighting for consumers’ attention. MX Player is Hotstar’s top rival, with a fully ad-supported business model. Large Indian broadcasters are following Hotstar’s formula of ad-supported free video for catch-up content, with subscriptions required for live sports and premium shows. Meanwhile, telcos such as Airtel and Vodafone are aggregating content from multiple platforms and providing a payment interface. Over 200 million Indian consumers stream video from telcos, which could grow to 375 million by 2021. It may play in Bangalore and Beijing, but will it play in Boston?

In contrast to the Asian model, most US streaming-video services take a subscription-only approach, in which users pay a monthly fee to access content ad-free. The two leaders, Netflix and Amazon Prime Video, are subscription-based, with the latter included in Prime membership. Both Disney and Apple have launched subscription-only streaming services, albeit with low monthly fees, intended to make the services no-brainers for customers.

The reality of subscription fatigue

The question remains – how many subscription TV services are consumers willing to maintain? Deloitte’s Digital Media Trends Survey, 13th edition, shows that consumers have an average of three streaming video services, a number that has remained steady for 2 years. How many spots are there on the podium? Certainly, consumers love having a choice of services, and avoiding ads is the top reason that consumers sign up for streaming video. Some viewers are especially ad-resistant, while others care less about avoiding ads than about maximizing their viewing options.

But for most consumers, the costs of having multiple video subscriptions – in both hassle and money – are adding up. Consumers are especially frustrated when their favorite shows disappear without notice, and by the reality that they must subscribe to multiple services to watch their favorite shows and movies. These factors make streaming services seem progressively less valuable to consumers – for the same (or a higher) price, they get less of what they want. The problem will get worse as media companies withdraw rights from competitors and launch their own streaming services. Finally, there are the economic costs of multiple services. For consumers who cut the cord to spend less than they would with a pay-TV bundle, three services could be the maximum.

The costs of launching subscription-only streaming services are mounting, too. The highest costs, as in China and India, are developing original content and obtaining rights to live sports. Netflix plans to spend USD 15 billion on original content in 2019 and nearly USD 18 billion in 2020, but in past years it has usually ended up spending even more than it had originally planned. Apple spent a reported USD 6 billion on original content for the launch of its Apple TV+ service. Sports rights, which Hotstar and the Chinese big three have brought to consumers, are also costly. Rights to broadcast National Football League games, the highest-rated sport in the US and the key to attracting young male viewers, cost networks about USD 6 billion per year, with big increases anticipated once the current contract ends in 2021. It is difficult to absorb these costs and make a profit from subscription fees alone.

The bottom line

TV may not be growing at the rate it did 20 years ago, but neither is it collapsing, and both advertisers and broadcasters need to think of it in those terms. TV ads, first of all, are not following the same path as some other traditional media ads. TV ad revenue is not dealing with multiyear double-digit declines. Global TV ad spending in 2020 is expected to grow in dollar terms (although usually losing share of the total ad market) in the Philippines, India, Brazil, Vietnam, Indonesia, Poland, Belgium, Japan, UK, Thailand, Canada, France, and Italy. And although it is expected to shrink even in absolute dollar terms in some markets (Australia, Germany, Spain, Netherlands, China, Denmark, Taiwan, and Singapore), the annual declines are moderate rather than severe, and they are still less than the declines in ad revenues for other kinds of traditional media. Interestingly, many of the higher-growth TV ad markets are also ones where antenna TV usage rates are the highest. It is worth noting, however, that the future of TV advertising is by no means certain. While one can be fairly confident about its growth in 2020 – Olympics plus the US presidential election make for predictable growth – the picture becomes cloudier as the industry peers further into the future. The total TV ad spend in 2021 should still be higher than in 2019, even if slightly lower than or flat with 2020 levels. For 2022 and later, the crystal ball becomes even murkier. Although it seems probable that the current trend will continue – basically flat TV ad revenues, with uplifts once every four years.

Focusing on antenna TV specifically, its surprisingly strong performance holds some interesting angles for broadcasters. One might assume that broadcasters would be indifferent to whether a viewer watches TV via an antenna or a pay-TV distribution mechanism, such as cable. As long as they are watching, and the broadcaster can charge advertisers for those eyeballs, who cares how the content is delivered? In fact, since ad skipping is likely less common on antenna TV, one might think that broadcasters would be pleased by antenna TV viewership growth. The reality is more nuanced. Prior to 1992, at least in the US, broadcasters would indeed have had reason to celebrate antenna TV’s resilience. But since then, in the US as well as other countries, distributors have been paying broadcasters retransmission consent fees. Thus, in countries where retransmission consent fees are material, a shift to antenna TV is better for broadcasters than losing viewers to cord-cutting entirely, but it is a mixed blessing. In countries without those fees, however, antenna TV is an absolutely good thing for broadcasters. With the growth of AVoD, hundreds of millions of viewers in 2020 are expected to make the same deal, willing to watch some percentage of advertising content in exchange for free, or at least discounted, quality-video entertainment. Based on all this, it looks like the future of TV will contain a mix of business models.

People across the world now spend the majority of their internet time streaming video, and the internet itself is segmenting into cloud-based services and CDN edge capabilities. Growth in live streaming video and the promise of streaming video games may further impact competition and innovation. These shifts have implications for a range of players: media companies, telecoms, and CDN providers. Media companies may view the current landscape as an incentive to move more content onto CDNs. However, this is by no means a simple decision. Broadcast and pay-TV are still strong, although slowing in some major geographies. In addition, deconstructing IPTV networks and STBs is not easy, nor is shifting an audience to potentially risky OTT services. Most media companies will likely run their OTT efforts in parallel with their broadcast and pay-TV services, allowing the market to determine which will draw the most subscribers.

For many media companies adding OTT to their strategic initiatives, the question becomes: how? Should they partner with a CDN provider? Do they expand on their existing relationships with networks that they have developed for streaming pilots? Or do they commit to building their own CDNs? The equation becomes more difficult when considering the potential competitive advantages media companies may find in controlling delivery and owning the value chain right down to the end consumer. Major media companies may choose to build their own networks to control the entire delivery pipeline – and to secure ownership of the data their audiences generate. However, only a few will likely have the capital to do so. The rest will probably rent capacity from CDN providers who, in turn, will pay telecoms to run traffic on their networks. The cost of renting distribution over CDNs is now very low, which can make renting an attractive option – as well as increase the pressure on CDN providers to expand margins by offering other services or applying event-based peak pricing models.

For their part, many telecoms already operate and lease access to CDNs. However, with margins on CDN rents narrowing, leasing CDN access to content providers may become less profitable. This may provide an incentive for telecoms that have purchased media catalogs to invest more in delivery capabilities around their own content. Yet telecoms are also building out appliances on cell towers and selling edge services. Can they sell CDN and edge services and still invest in differentiating delivery for their own content? Also, worth considering is that both CDN and edge services allow telecoms to offer their customers more sensing and analytics capabilities that can be translated into performance and innovation. Is there a clear path from controlling a private CDN to establishing competitive advantage around delivery and analytics?

Telecoms also control the last mile of content delivery to users. Can they parlay this last-mile control into value? If 5G becomes widely implemented and adopted, will it shift more power to the telecoms that control last-mile delivery? Will it open up room for richer media? As for CDN providers themselves, they will likely face more challenges with capacity, quality of service, load balancing, and demand prediction as more audiences shift onto streaming services. Similar to what has happened among cloud providers, competition could drive CDN rental prices down further. Top CDNs may also face greater market pressure to secure delivery of intellectual property against intrusion and theft. To address these needs, CDNs could put in place additional data analytics, machine learning, and potentially content blockchains to manage growing complexity – all of which would add to their operating costs. Computation storage and routing will likely prompt investments in hardware, while load balancing, stream optimization, demand prediction, and security may demand more software capabilities. On the other hand, while CDNs may face growing competition and lower margins for delivery, they may also expand as more cloud services migrate to the edge. Just as telecoms are dabbling in CDNs, the latter are spinning up edge computing services, not just for media, but also for IoT.

In Asia, ad-supported services will likely remain a pillar of video streaming. Ads provide much-needed revenue for services like the Chinese big three that seek to expand into new areas, such as gaming and music. Subscriptions will remain part of the mix for premium content, such as sports and original programs. However, ad-supported-only services will likely remain vital for consumers with little disposable income, and for whom catch-up TV, including sporting events that have already taken place, is enough.

In both Asia and the US, advertisers will likely move more of their spending to ad-supported services, attracted by millions of eyeballs, the ability to target individual consumers, and the certainty that their brands will be attached to professionally produced shows and movies – known quantities in comparison with user-generated content. Based on Technology, Media, and Telecommunications Predictions 2020 – a report by Deloitte Insights.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login