BCS Stories

The SPAC boom seems to be over

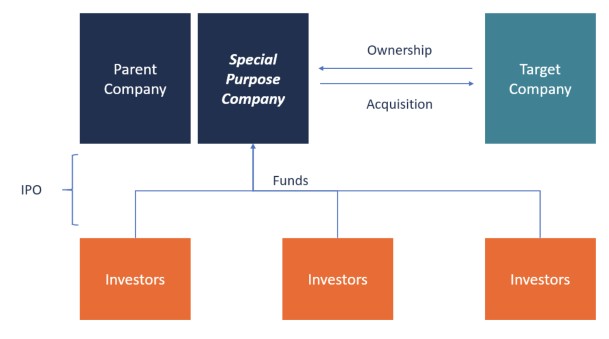

A special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) is a corporation formed for the sole purpose of raising investment capital through an initial public offering (IPO). Such a business structure allows investors to contribute money towards a fund, which is then used to acquire one or more unspecified businesses to be identified after the IPO. Therefore, this sort of shell firm structure is often called a “blank-check company” in popular media.

When the SPAC raises the required funds through an IPO, the money is held in a trust until a predetermined period elapses or the desired acquisition is made. Therefore, a SPAC doesn’t conduct any business, does not sell anything and typically only holds the money raised in its own IPO.

In the event that the planned acquisition is not made or legal formalities are still pending, the SPAC is required to return the funds to the investors.

Roughly 70 special-purpose acquisition companies have liquidated and returned money to investors since the start of December. That is more than the total number of SPAC liquidations in the market’s history, according to data provider SPAC Research. SPAC creators have lost more than $600 million on liquidations this month and more than $1.1 billion this year, the data show.

In India, Seven Islands Inc, a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) sponsored by James Murdoch and former STAR India CEO, Uday Shankar, has decided to abandon its earlier plan to raise $300 million through an initial public offering (IPO) in the US. Murdoch and Shankar decided not to pursue the SPAC route as they were interested in acquiring and building companies rather than pulling out after taking them to an IPO. the company has now decided to make its investments through investment company Bodhi Tree Systems, in which Shankar, James Murdoch (through Lupa Systems) and others have a stake.

Some India-sponsored SPAC players are going ahead, though. In October this year International Media Acquisition Group (IMAC), a SPAC sponsored by Shibasish Sarkar (formerly with Reliance Anil Ambani ) struck a deal to acquire Reliance Entertainment Studios and Risee Entertainment.

One characteristic of SPACs is that investors can get their cash back if they don’t want to participate in a deal. When the market was hot, investors often held shares in the newly public startups, expecting big returns or selling immediately if shares had already gone up. Now they are pulling out before the deals close, dramatically reducing the amount of cash companies can raise.

SPACs are now paying less for companies than they did during the sector’s peak. The average valuation of startups announcing SPAC mergers has fallen to about $400 million this quarter from more than $2 billion for most of last year, Dealogic data show. Roughly 300 companies have gone public through SPACs in the last two years.

There are still nearly 400 SPACs together holding about $100 billion that have yet to find deals, according to SPAC Research. If roughly 200 of the SPACs liquidated, the losses for creators would be well above $2 billion, said New York University Law School professor Michael Ohlrogge, who studies SPACs. SPAC creators have lost about $9 million on average through liquidations this year, money they paid to banks and law firms to set up the shell companies.

There are another roughly 150 SPACs holding about $25 billion that have reached merger agreements but haven’t closed them, including a blank-check firm that is trying to take public Donald Trump’s social-media company, according to SPAC Research. Some of those will likely get called off, meaning liquidation losses could end up being even greater than expected.

During the boom in blank-check companies, their creators couldn’t launch them fast enough. Now they are rushing to liquidate their creations before the end of the year, marking an ugly conclusion to the SPAC frenzy.

This year’s losses show why SPACs are inefficient for companies seeking to raise money or go public.